January 19th, 2017 marks the 1,000th day of what became known as the Flint Water Crisis. It has been days full of tainted water harmful to the people of Flint. On April 25, 2014, the city of Flint did something that would change the fate of the community forever. How did we reach day 1,000?

To see how the crisis began watch the video below

Before the crisis, Flint was put under the emergency manager law. This law allows the state to take away local power and place an emergency manager to fix a financial crisis. At the time Flint was broke, Darnell Early, Flint’s Emergency Manager, took over to cut costs in Flint. One decision made was to switch to the Flint River as a main water source. Prior to the switch, Flint was getting their water from a source in Detroit, which was quite costly. To lower this cost, plans were made to switch to the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) pipeline that ran straight from Flint to Lake Huron, but the only problem here was that the pipeline was not built yet. The plans to finish the pipeline would take at least 3 years, so in the mean time, the city voted to switch its water source to the Flint river to cut cost.

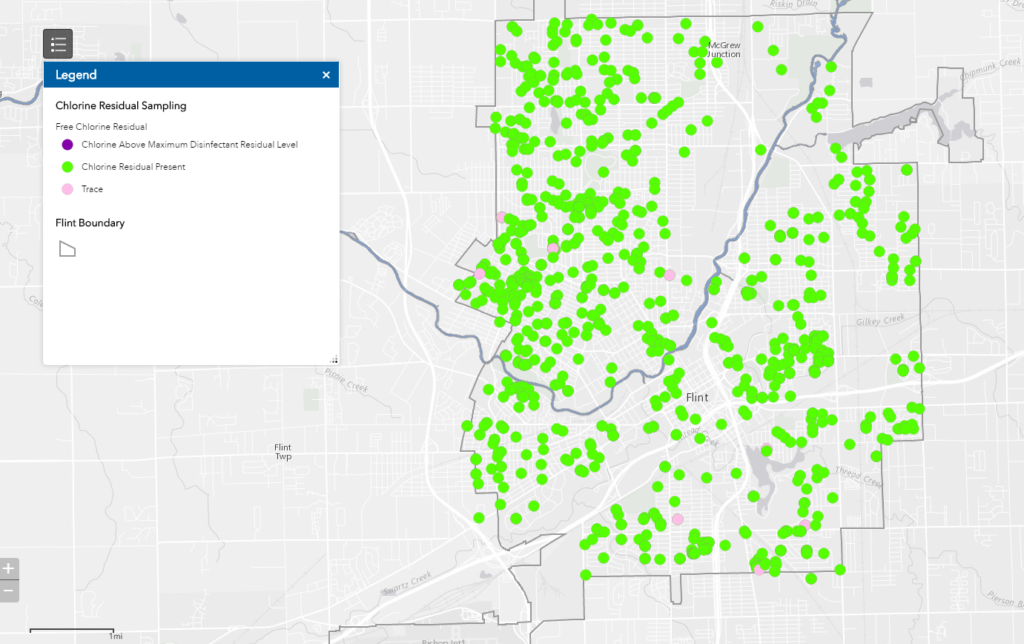

Soon after the switch, a crisis arose when boil-water advisories were issued because E-coli bacteria was found in the water. Not long after, another advisory was released with warnings of Coliform bacteria. To combat these bacteria’s found in the water, the city had to up chlorine levels which then lead to high levels of TTHM (total trihalomethanes). These chemical compounds form when organic matter reacts with the chlorine disinfectants. People in Flint started to get rashes and become sick. On top of that, water bills were raised. After continuous water warnings, Flint was beginning to loose trust in their government and the water.

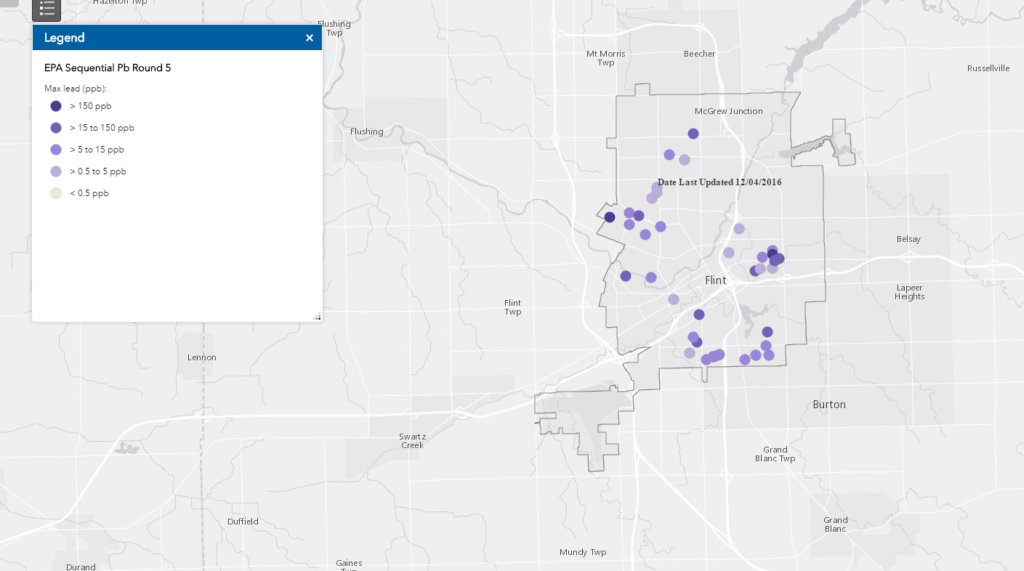

Odors, a discoloration in the water, and health issues became a common problem in Flint homes. People of Flint started to reach out and raise concerns, but the city, state officials and local media were not listening. Therefore, they took matters into their own hands. Flint mother, Lee-Ann Walters had demanded for her water to be tested and had discovered 104 parts per billion of lead in her water. She had contacted Miguel Del Toral, a manger at the EPA’s Midwest water division, to inform him that the water plant was not treating the water with the correct corrosive controls leading to the lead problem. After Del Toral had been informed of these results he decided to look into the concerns further and had found that the MDEQ was illegally not using corrosive control in the water. He had informed the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and MDEQ ( Michigan Department of Environmental Quality) of his concerns. Once the concerns were presented, he was silenced, he was then advised not to talk about Flint or to anyone from Flint. Outside of work Del Toral had released his findings to Walters and water expert Dr. Mark Edwards.

To see how government handled the crisis watch the video below

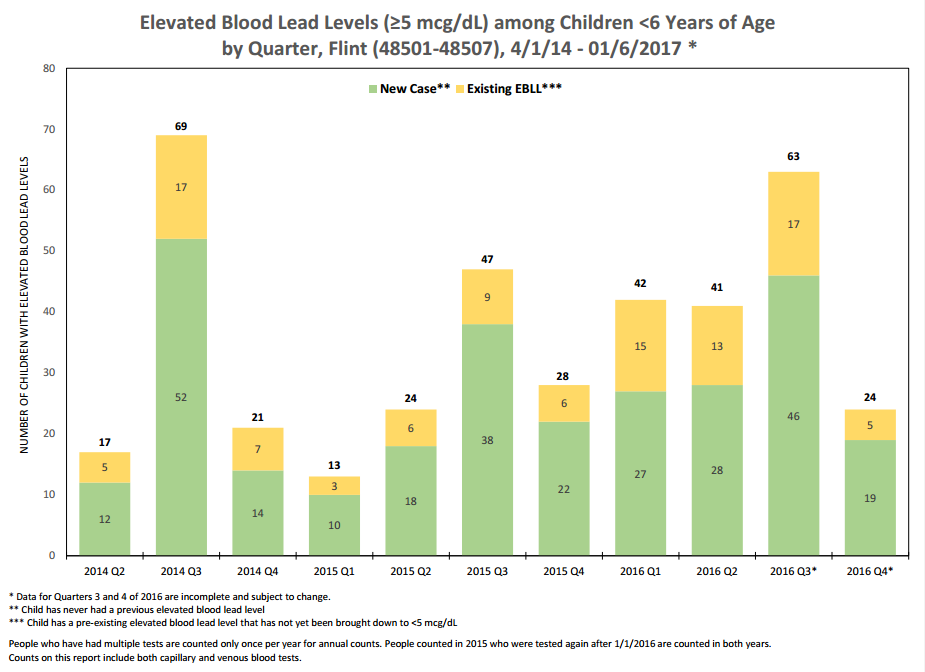

On September 15, 2015 these results were released to the public and it was confirmed that alarming amounts of lead were in the water all throughout Flint. Around the same time, the city and state began to notice a huge incline of lead in children’s blood levels. Even after these finding, the state had neglected to let the city know of the issue, but after Dr. Monna Hannh-Attisha had publicly raised these concerns, a health emergency was put into place. Flint was told they could no longer use their water, still had to pay the high bills, and now had to buy bottled water. Beyond a lead crisis, a government crisis arose.

To learn about lead in the blood

See how the crisis was more than a lead problem

Once learning that families were experiencing lead poisoning and that the water was not being treated correctly, it was undeniable that Flint needed to switch back to the Detroit pipeline. The switch back would take $15.35 million dollars. Governor Snyder signed a bill granting $9.35 million from the state, Flint would have to pay $2 million, and the Mott foundations pledged $4 million dollars to fund the switch back.

Not only was there a lead crisis, but it was also discovered that there was a huge outbreak of legionnaires’ disease. In fact, there were 12 deaths do to the disease, and the main suspect was the Flint river. The yearly average of cases of Legionnaires’ disease is 12. From June of 2014 to November of 2015 there were 91 cases in Genesee County.

To learn more about legionnaires’ in Genesee County watch the video below

Once they switched back, the EPA and other sources started keeping a close eye on the water. The data being collected is showing a trend of better results, but after all Flint has been through they just can’t seem to trust the government. To bring hope back to Flint, President Obama made a stop in the city, ensuring better lead results and security in using filters. The only question left is was Obama’s reassurance enough?

Learn more about Obama’s visit to Flint watch below

See how Flint reacted to Obama’s visit watch below

Nonetheless the crisis is NOT over. People in Flint still cannot use their water. The children still have lead poisoning, rashes, bone weakness, hair and teeth loss, and more.

To see families living with the crisis in 2017 watch below

Flint still has a long way to go when it comes to being fixed. This is a process that will take years, if not decades. The plan to replace lead pipes is predicted to take at least three years to finish. Kids in Flint with lead poisoning will need years of healthcare and special education. These plans will only follow through if Flint can manage to get the funding they need. The water plant needs an estimated $60 million alone to be able to treat raw water from the KWA pipeline. This plan for the water plant will also take some time, the best case scenario is to take three years for renovations. Typically, these kinds of renovations take close to ten years.

Learn more about Flint’s reaction to testing results

Latest testing results

To see the governors Snyder promises to Flint watch below